At Butch Woolfolk’s home in Houston, the plaques he earned for running track and playing football at Michigan sit side by side. The awards commemorate a stretch in the early 1980s when Woolfolk, now 62, earned All-American honors in both sports. Decades later, he’s still the last Wolverine to accomplish that feat.

On the gridiron, where Woolfolk starred at running back for coach Bo Schembechler, he finished as the program’s leading rusher with 3,861 yards before the New York Giants selected him in the first round of the 1982 NFL draft. On the track, where Woolfolk was one of the most decorated high school sprinters in the country, he won a handful of Big Ten titles and finished sixth nationally in the 200-meter dash in 1980.

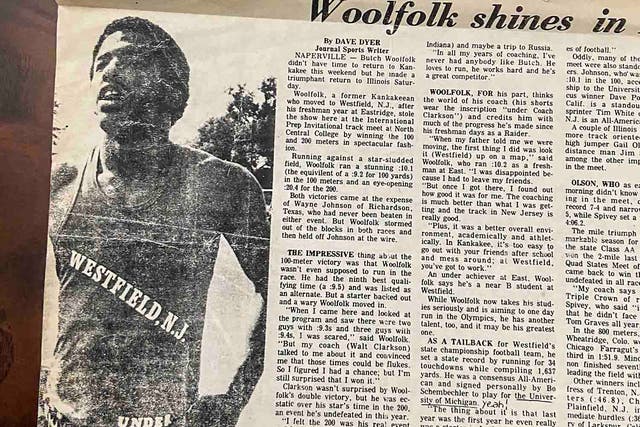

But tucked away in a photo album is a newspaper clipping that means more to Woolfolk than any award in his collection. The article recaps his performance at the International Prep Invitational track meet in 1978 when Woolfolk captured the 100- and 200-meter titles after running the “fastest schoolboy times in the nation,” according to his biography at the Westfield Hall of Fame in New Jersey.

Butch Woolfolk drew acclaim as a high school sprinter while also signing to play football at Michigan. (Photo courtesy of Butch Woolfolk)

“And it’s the last time I’ve ever seen myself as the best that there was,” Woolfolk said in an interview with FOX Sports. He added: “I look at that occasionally and I always say, ‘What if?’”

As in, what if Woolfolk could have dedicated more time to achieving his dream of qualifying for the 1980 Olympics? What if the two sports he competed in at Michigan didn’t have such conflicting demands? What if he found an equilibrium in his athletic pursuits?

Woolfolk remains among the most successful football players to double-dip in track for the Wolverines, a list that includes Braylon Edwards, Denard Robinson, Tyrone Wheatley, Desmond Howard, Harlan Huckleby and Thomas Wilcher, among others. But almost all of them were confronted with the reality that football in Ann Arbor is king, that the sport providing their scholarship will dictate the schedule, that joining the track and field team is amenable for athletes wanting to scratch a competitive itch but proved untenable for anyone craving an even partnership — especially if reaching the NFL is a primary goal.

Conversations about someone bucking that trend have intensified during Michigan’s recruitment of Nyckoles Harbor, a 6-foot-5, 245-pound wunderkind from Archbishop Carroll High School in Washington, D.C., where his coaches have described him as a generational talent akin to the great Bo Jackson. Just 17 years old, Harbor is simultaneously a five-star prospect on either side of the ball and one of the fastest sprinters in the nation with personal bests of 10.22 seconds in the 100-meter dash and 20.63 seconds in the 200-meter dash. Both marks rank among the top 12 times for high schoolers this year.

Harbor intends to pursue both sports in college and would face similar obstacles wherever he commits. He is rated the No. 16 overall player in the 247Sports Composite rankings for the 2023 recruiting class. He remains the most coveted prospect on head coach Jim Harbaugh’s board despite postponing his commitment to the February signing period, at which point Michigan, South Carolina, LSU, Maryland and Miami are among the schools hoping to land an athlete uniquely positioned to answer the what ifs.

“I don’t see a reason why I can’t … be the number one pick in the NFL draft and then train in the offseason for the Olympics and do that, too,” Harbor told The Washington Post earlier this year (He did not respond to interview requests for this story). “Obviously it is going to be hard. A lot of people say that I’m the most talented person that they’ve ever seen, so why can’t I be the first to do this?”

*** *** ***

A single YouTube search for Harbor’s name elicits a fascination with his athletic gifts. The videos have titles like No HS Football Player this size has ever done this! and THE SCARIEST RECRUIT IN 2023!, with hundreds of thousands of combined views and commenters that describe him as everything from the first person deserving of a six-star ranking, to an escapee from some government lab in nearby Langley, Virginia, home of the CIA.

It’s difficult to contextualize a teenager who is so big and so fast.

“Nyckoles Harbor has the fastest max speed on record for any athlete taller than 6-2,” said a tweet from the sports technology and data company Recruiting Analytics, “with a verified max speed of 22.1 mph.”

Debates continue to rage about Harbor’s best position at the next level. Some envision him as a defensive end or outside linebacker careening off the edge with the kind of force that torments offensive tackles and terrifies quarterbacks. (Harbor racked up 22½ sacks and 47½ tackles for loss in his junior and senior seasons at Archbishop Carroll.) Others see a field-tilting offensive weapon who blends a tight end’s size with straight-line speed comparable to Kansas City Chiefs wide receiver Tyreek Hill, who ran a personal best of 10.19 seconds in the 100-meter dash at Garden City Community College. (Harbor caught 31 passes for 729 yards and 10 touchdowns in the last two years combined.)

Sources familiar with Michigan’s recruitment of Harbor said the coaching staff originally viewed him as an edge rusher who would be given chances to contribute on offense. But Harbor’s personal preference is believed to be offense, where the physical demands and snap counts aren’t as taxing — especially at wide receiver — and there would be less pressure to add the kind of bulk that might hinder his development on the track. Early recruiting overtures from defensive line coach Mike Elston and defensive coordinator Jesse Minter have been swapped for efforts by wide receivers coach Mike Bellamy, who is now the lead recruiter, and Harbaugh.

“If I’m him,” said Edwards, the No. 3 overall pick in the 2005 NFL draft who spent one year on the track and field team, during an interview with FOX Sports, “I gotta ask myself a question: Do I wanna go to the NFL, or do I want to seriously have this dream of football and track? If I want to seriously have this dream of football and track, you gotta play wide receiver. If you want to go to the NFL, you’ve gotta play tight end or defensive end.”

There are natural ties connecting Harbor with Michigan that form the bedrock of his connection with the Wolverines. The athletic director at Archbishop Carroll is Brian Ellerbe, who was the men’s basketball coach at Michigan from 1997-2001. One of Harbor’s private track coaches, Pamela Crockett, is a Michigan alumna. A former teammate of Harbor’s, Ziyah Holman, now runs for the women’s track and field team at Michigan. Harbor’s parents, Azuka “Jean” Harbor and Saundra Harbor, have placed a heavy importance on the educational side of college given their career experiences as a former biochemist for NASA and a pharmacist, respectively. (Saundra Harbor reportedly grew up in Michigan as well.)

Nyckoles Harbor believes he is capable of being the No. 1 pick in the NFL Draft and competing in the Olympics. (Amanda Andrade-Rhoades/For The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Harbor and his mother took an unofficial visit to Ann Arbor in the fall of 2021 and returned with Harbor’s father, an ex-forward on the U.S. men’s national soccer team, for an official visit that coincided with Michigan’s win over Maryland in late September. The arrangements for each trip reflected the duality of Harbor’s athletic interests, as the football and track programs worked together in a joint recruiting effort. Harbor’s de facto host for the official visit was Robinson, who ran one year of indoor track before developing into an All-American quarterback. When Harbor posed for photos at Michigan’s track and field complex, staffers from both teams were there to watch.

A dazzling indoor track facility has become an important tool for Michigan when recruiting athletes like Harbor who are also considering schools in warmer climates. The building, which is located on the university’s south campus, was part of an ambitious $168 million renovation to improve the resources for Olympic sports. Ideas for the indoor track and field center, which opened in 2018, were gleaned from both domestic and international arenas to produce custom features like a hydraulic, banked 200-meter competition track surrounded by a 300-meter practice track, with additional sprint lanes and jump runways across the infield.

The climate-controlled structure offers a comfortable training environment to offset Ann Arbor’s average snowfall of 43 inches per year.

“It’s easy to say, ‘Well, I can only do certain things in a certain climate or a certain location,’” said Steven Rajewsky, an assistant track coach at Michigan, during an interview with FOX Sports. “But I think there’s enough schools like Michigan that show you can do it and it has been done.”

*** *** ***

Seven weeks before reporting to Michigan, Robinson savored what he thought was the capstone to his track and field career for Deerfield Beach High School at the 2008 Florida 4A State Championships. He finished third in the 100-meter dash and ran anchor for a 4×100-meter relay team that posted a season-best time of 41.37 seconds to snag first place.

From that point forward, Robinson, a four-star recruit, intended to focus on football for the Wolverines. Running collegiately never crossed his mind until then-Michigan track and field coach Fred LaPlante dropped by a football practice and encouraged Robinson to try both sports. After several nudges, Robinson asked head coach Rich Rodriguez for permission to join the indoor track team after football season.

“If Denard wanted to do it,” Rodriguez said in an interview with FOX Sports, “I was all for it.”

The only stipulation was that Robinson still had to participate in the football team’s winter workouts — a decree levied by every coach whose dual-sport athletes commented for this story, from Schembechler (1969-89) to Lloyd Carr (1995-2007) to Rodriguez (2008-10). And that meant Robinson’s schedule looked something like this: daily 5 a.m. wake-up calls for football strength and conditioning; academic classes throughout the morning; track and field practices around midday; late-afternoon rehab sessions in the football training room; study hours in the academic center each evening.

“I was 18 years old,” Robinson said during an interview with FOX Sports, “so I could go all day.”

Fatigue and scheduling challenges proved less problematic for Robinson and other former Wolverines than the ubiquity and suction football had on their lives. Winter workouts and spring practices gave their primary sport a year-round feel, and the constant push to add muscle mass each offseason cut against the way Michigan’s track and field athletes trained. They were forced to maintain bulky physiques for football rather than transforming into lithely-built sprinters.

Denard Robinson set track aside to improve his odds of winning the starting quarterback job at Michigan. (Photo by Leon Halip/Getty Images)

Most of them reached a point where choosing between football and track became inevitable, and there was never much doubt which sport would win:

— Robinson, who recalled Rodriguez bringing recruits to some of his Michigan track meets, remembers needing to be massaged and stretched in the team hotel prior to the Big Ten Indoor Track and Field Championships in 2010 after some of the most arduous football workouts of the offseason earlier that week. “I felt like they kind of did me dirty,” Robinson said. He finished one spot shy of the 60-meter finals and spurned the chance to run outdoor track to improve his odds of winning the starting quarterback job in spring football.

“A different position and you can be in both sports,” Robinson said. “I mean, RGIII did it (former Baylor quarterback Robert Griffin III). But his (track) coach had worked out a deal even before he got there. I didn’t have that same luxury with me running track.”

— Woolfolk, who said Schembechler promised he could skip spring practice to pursue Olympic qualification, grew disappointed and heartbroken when football attendance proved mandatory. He still advanced to the Olympic trials for the 200-meter dash but remembers getting “my doors blown off by guys that I had beaten in high school that were now on top because they strictly paid attention to track.” Rather than argue with Schembechler, Woolfolk played four years of spring football in addition to running track for coach Jack Harvey. The physical toll of football diminished his speed and interest in the sport he loved most. Woolfolk redirected his attention toward a potential career in the NFL instead.

“Coach Harvey was intimidated by Bo,” Woolfolk said. “In fact, the couple times I would leave spring ball to go over there and practice, he would say, ‘Are you OK? Don’t let Bo catch you over here,’ like he would get in trouble. It was something that Bo really controlled. He owned everything and he knew where I was.”

“I have not come to peace with it,” Woolfolk added. “I agonize over it all the time.”

Butch Woolfolk believes he could have competed in the Olympics if he had been able to give track enough attention. “I have not come to peace with it,” he said. (Photos courtesy of Butch Woolfolk)

— Edwards, who asked about competing in both sports during his recruitment, said Carr was amenable if football responsibilities were properly handled. “There’s always an if,” Edwards said. A sprinter and high jumper, Edwards said he conditioned himself to view track and field as a vessel through which he could become a better football player. That was the rationalization Edwards needed when discrepancies in training made it difficult to manage his weight. Carr nixed the multi-sport arrangement after Edwards’ freshman season.

“If you’re giving a kid a scholarship,” Edwards said, “you want to see that kid. You want to see that kid in the training room. You want to see him in the weight room. You want to see him watching film. You want to see him just walking around with his teammates.

“So I think that was the hardest part is players not seeing me and being like, ‘Ah, man, he gets special privileges?’ And I think the coaches were (like), ‘Is he taking football serious? Is he still knowing his playbook? Is he getting ready for next season?’

“Those were the two hardest parts is weight fluctuation and not being around the facility for coaches to see you daily.”

*** *** ***

Last June, long after his team completed spring practice, Harbaugh spoke with reporters at a recruiting event in Big Rapids, Michigan.

Harbaugh was asked about the only player on his roster still competing well past the semester’s end: linebacker Joey Velazquez, whose moonlighting on the Michigan baseball team produced some clutch hitting to aid the Wolverines’ postseason run.

“You know my love of multiple sports, guys that play multiple sports,” Harbaugh said as a smile stretched across his face.

There’s little question Harbaugh would support Harbor’s dual-sport ambition if the phenom commits to Michigan. In addition to his adulation for Velazquez, who plays mostly special teams, Harbaugh routinely mentions how impressed he was with quarterback J.J. McCarthy’s hockey background while preaching the importance of younger athletes sharpening their skills across multiple disciplines. And in Harbor’s case, the outlandish talent of the player in question likely warrants greater latitude than previous football coaches were willing to offer.

“I don’t know how good I could have been,” Butch Woolfolk says. Can it be different for Nyckoles Harbor? (Photo courtesy of Butch Woolfolk)

Most of the Michigan football players who ran track lacked the Olympic potential many believe Harbor possesses, though Woolfolk was clearly an exception to that rule. Harbor’s time of 10.22 seconds in the 100-meter dash would have produced a ninth-place finish at the 2022 NCAA Championships, and his 200-meter time of 20.63 seconds would have been good enough for eighth. Even without accounting for race conditions, the extrapolations are staggering for a teenager who ran those times before his senior year of high school.

“Olympic speed and he has prototypical NFL size,” said Edwards, who, like Robinson, enjoyed being part of the track program despite the brevity and challenges of their respective experiences. “I think he’s in a class of his own and I think this is a different day and age.”

So what if?

What if Harbor finds a way to dominate the football field without sacrificing the potential he’s shown on the track? What if he balances the strength and power of a game-changing tight end with the explosiveness of an elite sprinter? What if Harbor goes to Michigan and does what his predecessors never could?

“That question will always be there,” Woolfolk said. “The burning sensation that’s inside of me is I don’t know how good I could have been.”

Read more:

Top stories from FOX Sports:

Michael Cohen covers college football and basketball for FOX Sports with an emphasis on the Big Ten. Follow him on Twitter at @Michael_Cohen13.

Get more from College Football Follow your favorites to get information about games, news and more