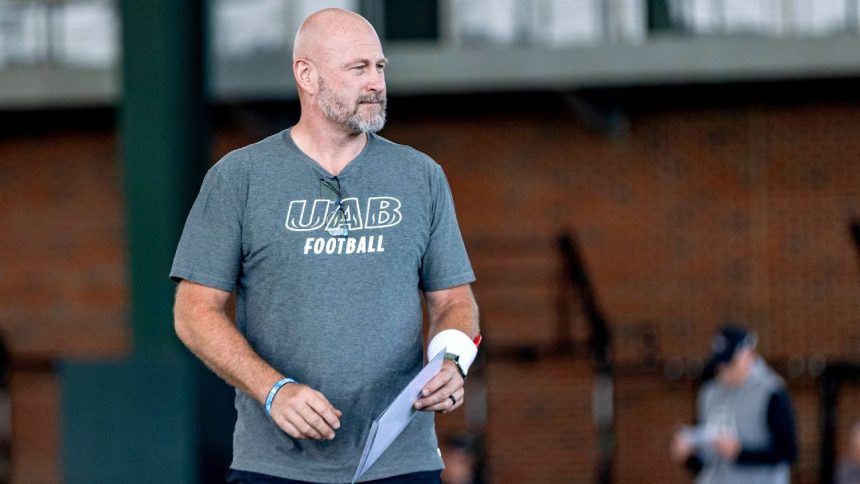

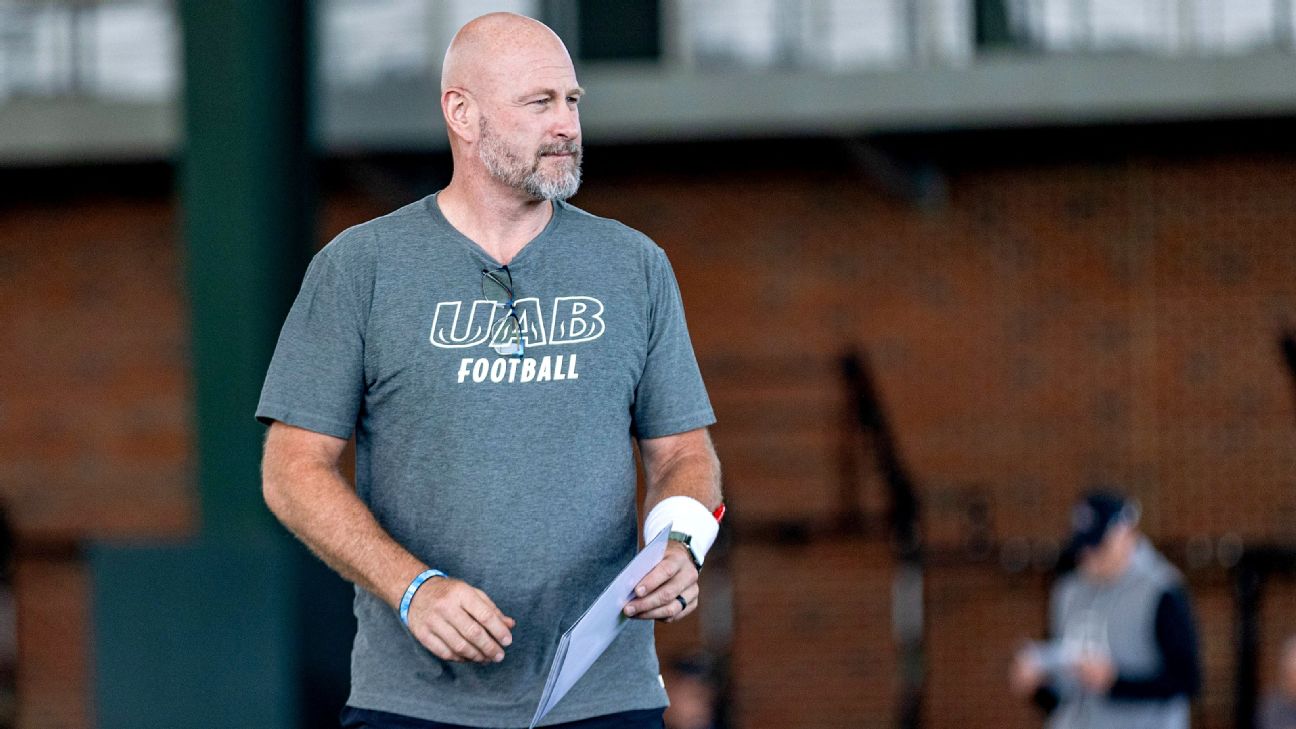

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. — Trent Dilfer stands in his office doorway in late July, a cheerful grin and a firm handshake obscuring the faint redness in the corners of his eyes.

College football’s most outside-the-box new hire — who isn’t lacking for name recognition thanks to his time in the NFL and on television but whose actual coaching experience is limited to four years at a small private high school in Tennessee — doesn’t reach for his coffee once as he spends the next hour and a half excitedly laying out his vision for UAB football.

The College Football Playoff graphics dotting the walls around the facility might be too subtle a nod to Dilfer’s aspirations. The 51-year-old former quarterback talks about competing for titles out in the open and at full volume — bold for a program that has forever been defined by its limitations rather than the potential of what it could be if only it controlled its own destiny, if only it had more support, if only it had better resources.

Take the previous night’s return trip from American Athletic Conference media day in Texas. Dilfer says he could have easily thought, “Damn, this would have been so much better if we could have flown private.” They could have had an extra staff meeting, but no. “I was on an American Airlines flight with my players, sitting in TSA while [USF coach Alex Golesh] is on a private jet. I don’t give a s—. I’m here this morning. I got two hours sleep. No big deal. We’re going to crush it!”

Dilfer brings up Golesh’s transportation advantage again later and turns to his communications director. “He’s keeping track of all that stuff,” he says. All the little inequities. All the perceived slights they’ll remind players of during camp. Dilfer feeds off the stuff. It’s the essence of his origin story — how a kid from California’s Central Coast ended up going to Fresno State rather than USC or UCLA, how he went from first-round flop to Super Bowl champion.

He has a sign on his door that doubles as a staff mantra: “UAB football. No problems … only solutions!”

All Dilfer sees, for better or worse, are opportunities.

So when he heard nearly every coach stand up at AAC media day and complain about the impact of NIL and the transfer portal, he smiled. It was a reminder that his staff’s inexperience might double as its superpower. Let all those other coaches remain hopelessly in love with what college football used to be, Dilfer says. He and his assistants don’t know anything other than today’s turbulent landscape — “and that’s an advantage.”‘

“I love the challenges because with challenges come solutions,” Dilfer says. “How do you compete against a collective of $16 million when you have $100,000? We’re going to find a way. I’m not going to b—- about it. I’m not going to magically raise $16 million or $6 million. I don’t know if I’m going to raise $600,000. But we’re going to find ways to win.”

UAB has always required doing more with less. But the gap between the haves and have-nots is widening. And the best that can be said for the administration’s commitment to doing what it takes to remain competitive is: We’ll see. It took a massive donor-based fundraising effort to bring football back after it was shut down late in 2014, and momentum has long since fizzled.

Dilfer might have the personality to reignite that fire. He might see a way to something no one has before. Or he might be blinded by his own ambition.

We’ll see.

DILFER HAS A self-deprecating streak that’s disarming. He downplays his talent constantly; never mind he lasted 13 years in the NFL and made a Pro Bowl. He scoffs at the Deion Sanders comparison — another former pro who jumped into college with no experience. “We’re playing with a different deck of cards,” Dilfer says. Never mind the replica Lombardi Trophy in his office or the championship ring in his backpack. “There’s not one recruit coming here that knows anything about my career,” he says.

Sure. But there’s a reason UAB athletic director Mark Ingram went from being dead set against hiring a high school coach to bringing in Dilfer as maybe the most shocking move of the coaching carousel. Ingram says the difference was Dilfer’s NFL experience, his visibility on TV — including nearly a decade with ESPN — and his time as a coach with Elite 11, the annual quarterback camp.

During Dilfer’s introductory news conference, he wasn’t bashful about pointing out his own lack of qualifications: how he wasn’t well versed in the history of the program; how he was a high school coach at his core, skeptical of any college job; how “I’d be lying if I told you I know how to recruit at an elite level.”

“I will hire people that have figured out-ness,” he said. “Yes, I made up that word. I think I made it up on TV one night when I was tired at ESPN and people laughed. I want people that can figure stuff out.”

Don’t let the aw-shucks routine fool you. Dilfer, who took over Lipscomb Academy when it was 2-9 and finished his fourth season with back-to-back state championships, counts himself among the people who can figure stuff out. He actually spent the past few years toying with what a move to college would look like. That’s because, he admits now, he was in the mix for some jobs before.

“When I had to entertain a couple of these things, I had to … be prepared,” he says. “When I talk to a president, I don’t want to just be the ex-athlete who says, ‘I played football, I can go coach.’ I want to have a coach’s book. I want to have a shell staff put together. I want to have a philosophy. I want to have core values.

“So, yes, it came out of nowhere. But never at one point was I not prepared.”

He knew he couldn’t attract (or afford) position coaches or coordinators from the country’s top programs, so he did maybe the next best thing: He hired the coaches who supported them behind the scenes. He brought in Georgia analyst Eddie Gordon to coach the offensive line, South Carolina analyst Nick Coleman to coach quarterbacks and Ohio State analysts Reilly Jeffers and Miguel Patrick to coach tight ends and defensive linemen, respectively.

“Alex is obviously the golden jewel in that,” Dilfer says.

That would be Alex Mortensen, who is something of a deep-cut in football circles — the longtime Alabama analyst who had a prominent role in tutoring quarterbacks Jalen Hurts, Tua Tagovailoa, Mac Jones and Bryce Young. Many coaches tried and failed to lure Mortensen away from Nick Saban, but Dilfer succeeded by making the 37-year-old an offensive coordinator before he’d ever held an on-field coaching title in the FBS.

Dilfer then took something else from Alabama, replicating Saban’s army-sized support staff by hiring two quality control coaches for every position coach. Dilfer had only $2.5 million to spend on his staff, so to make up for the shortfall, he says, he contributed $500,000 of his own $1.3 million salary. Even then, he says, everyone had to accept making less than the going rate.

The result is what Dilfer calls a hybrid approach: a Power 5-style staff with Power 5 credentials, but a Group of 5 work ethic.

“You’d be an idiot not to know why Nick does some of the things he does,” he says. “I put Kirby [Smart] in that, I put Ryan [Day] in that, I put Chip Kelly in that, I put Lincoln [Riley] in that. There’s a handful of guys out there that are the very best of what they do. So you want to know kind of their why’s, but you also have to be realistic with where you’re at and making it your way there.

“Head coaches are probably the most overrated people in football right now, except for one thing: Who they hire. I couldn’t be more pleased with staff — the auxiliary staff, operations, the people I kept. You know, you surround yourself with great people and the rest kind of takes care of it itself, to be honest with you.”

There’s a phrase Dilfer likes to use on social media, which is etched on his office window: “Fire breathers only.” While it ties in nicely to UAB’s mascot — a dragon — not everyone on staff can offer an exact working definition. But it boils down to, If you’re not burning with passion, get out.

Mortensen’s all in. The appeal of recruiting the Southeast and working with Dilfer, whom he knew through the Elite 11, was too compelling to turn down.

“There are people that have visited us, they keep commenting on the energy,” Mortensen says. “And I know it’s a little bit subjective sometimes, but I think there’s something to it and I feel it myself.”

A lack of returning starters on offense is “daunting” and leveling up to the AAC won’t be easy, Mortensen says, but he’s careful to note that the program they inherited wasn’t in shambles.

“There’s a high ceiling, really good foundation. But I also acknowledge there’s a lot of work to be done.”

THE WEEK-AND-A-HALF long handoff from interim head coach Bryant Vincent to Dilfer could have been rough. Vincent, who was suddenly out of a job after hoping to be retained full-time, offered his office to Dilfer at first. But Dilfer said no, they’d share the space while Vincent prepared the team for the Bahamas Bowl.

So Vincent got the big desk and Dilfer roamed, sometimes using an end table to jot down notes, sometimes sitting on the couch with a computer on his lap quietly studying.

“It was awkward,” Dilfer says.

Vincent doesn’t disagree.

“As the days went, I grew to like Trent,” Vincent says. “We built a relationship where we still talk today.”

Dilfer credits Vincent for his graciousness in giving him the lay of the land — and for connecting him with former coach Bill Clark, who retired last summer following major back surgery. Clark had as much invested in UAB football as anyone, maybe more. He stayed on through the shutdown and built the program back into something unthinkable: a winner, complete with two conference titles (the only ones in school history) and five bowl berths (again, the only ones in school history at the time).

“What really happened is I don’t think Bill thought this was a very good hire,” Dilfer says.

That checks out.

“I think anybody that’s a coach believes there’s a lot that goes with experience, and obviously that was concerning,” Clark says, “I mean, I think anybody that saw the hire would say the same thing.”

Clark admits he was skeptical and uncomfortable with the idea of someone learning on the job. But he accepted Vincent’s introduction and came away from meeting Dilfer impressed by his intelligence and enthusiasm.

Whether he succeeds or not, Clark says, “I don’t think it’s going to be a lack of energy or effort or caring.”

Dilfer is unapologetic in how far he’s willing to go. For the second time in 48 hours, he says that if opposing coaches keep tampering with their players, he’s willing and ready to hand over evidence of the illegal contact they’ve made via social media apps. Matter of fact, he says he has a noon appointment with someone from the NCAA’s NIL working group to talk about it. He claims that other coaches haven’t spoken up because they’re afraid of being blackballed and losing out on the next high-paying job. “I’m highly ambitious to make this a special place,” he says, “but I don’t have ambition beyond this.”

Time will tell how true that is.

Time will tell how good a tactician Dilfer is. The same can be said for his ability as a recruiter. His staff isn’t exactly loaded with coaches who have long-standing connections to Alabama high schools. UAB has eight commits, according to 247Sports, and none are from in-state (whereas 60 players on the current roster are). But it’s early and those connections can still be forged.

Then there’s the unmovable elephant in the room, which is literal in the case of the University of Alabama and its ivory-tusked mascot. As the flagship institution in the University of Alabama System, the Crimson Tide practically have a blank check while the Blazers — part of that same system — pinch pennies. Past coaches have come into the job on fire only to end up worn down by the constant struggle for basic necessities, whether it’s paying for players’ extra summer school credit hours or getting stipend checks on time.

Dilfer isn’t naive to those realities, but he hasn’t had to live them day in and day out yet. The hope among former staff is that athletic director Ingram will go to bat for Dilfer in a way that he didn’t for Clark, whom he didn’t hire, and Vincent, whom he had no choice but to accept as interim coach after Clark’s one-two punch of retiring so close to the start of the season and then taking it upon himself to name Vincent as his replacement.

Dilfer has tried to rally important stakeholders to his corner. He says he had to win over “Bill’s guys” early on — the core group of boosters who helped resurrect the program — some of whom he rattles off by name: Tommy Brigham, Hatton Smith and Craft O’Neal.

Moments before this interview, Dilfer hosted former UAB player and Athletics Foundation board member Justin Craft in his office for some face-to-face time.

“I’ll take on the fragility of what this place has been through,” Dilfer says. “But I don’t want [coaches] to worry about it because then it could get into a lot of problems — you could get into instead of challenges, problems. You could get into the whining, the complaining, the woe is me instead of looking forward.

“To a fault, I don’t have a rearview mirror. What I do have is a sense of history.”

There’s another distinction Dilfer makes.

“You can be aware of what’s behind you, but you’re not staring into it, being consumed with it.”

🎙: All-Access with Head Coach Trent Dilfer at the UAB Spring Game#WinAsOne | @DilfersDimes pic.twitter.com/MDwLJZLFZG

— UAB Football (@UAB_FB) April 7, 2023

DILFER IS CAREFUL when he describes the current state of UAB football. What he’s doing, he says, is not a rebuild. That would be a discredit to what Clark and Vincent accomplished — the games they won and the players they recruited. The physical infrastructure is already in place, including a new football facility and downtown stadium.

What Dilfer’s doing, he says, is more akin to a remodel. He wants to change the vibe of the place — how it looks and feels, and what it dares to accomplish.

The roster has turned over some since Dilfer took the reins. But on a scale of 1 to Deion Sanders, the 22 total transfers out of the program is relatively modest. Dilfer and his staff brought in 16 transfers, 12 of which have spent time at Power 5 programs.

Former Baylor quarterback Jacob Zeno figures to be the Week 1 starter. Together with Mortensen, Dilfer says they’re going to run stuff on offense that no one is prepared for. Zeno expects much more of an emphasis on the passing game than in years past, with a mix of outside zone, run-pass option and traditional drop-back passes.

“My expectation is like everybody else in the building — coaches, players — is to win every game,” Zeno says.

UAB received the eighth-most points in the AAC preseason media poll of its 14 member schools. So maybe a conference title is a ways off.

Asked exactly how good he believes they’ll be this season, Dilfer says, “I don’t have a crystal ball.”

But what he does have is the kind of enthusiasm that makes you forget he’s operating on just two hours sleep.

“Winners are about it, they don’t talk about it,” he says. “When you leave this office, I will do something to help us win. On the plane yesterday, I was doing something to help us win. On vacation, I was doing stuff to help us win. I have 48 staffers in this building and every single day they’re doing something to help us win. Now, they’re not talking about it, they’re actually doing it. That’s not true in every building. That’s not true in the NFL. That’s why you have the haves and the have-nots in the NFL. The people that win every moment of every single day, they’re doing something that when you add up the cumulative effect, it’s going to pour gasoline on your progression of winning.

“I’m trusting that process. We do winning things around here nonstop.”