BIRMINGHAM, Ala. — Rickwood Field is a place in which it’s possible to escape reality.

The original concrete wall added to the field in 1928, for instance, compelled individuals visiting the ballpark to stop, stare and think. When was the last time we saw groups of people completely halting their fast-paced lives to gawk at an outfield wall? The listed outfield dimensions (470 feet to left field, 478 to center and 335 to right) invited people to wonder how any ballplayer, even sluggers like Willie Mays and Josh Gibson, could park home runs over it.

The towering black-and-white scoreboard was an unequivocal connection to the Negro Leagues players that depended on it to count their stats and signify their wins and losses. The hunter-green grandstand, now the oldest baseball grandstand inside America’s oldest ballpark, enveloped the field like an embrace. The early 20th-century style of Rickwood Field was reflected in the advertisements pasted on the outfield walls, in the smaller and lower dugouts, and the colossal light towers that seemed to kiss the clouds. Once inside the compound, it was hard to think about anything but Rickwood.

Like walking into a dark and air-conditioned movie theater on a hot summer day, or diving into a book that’s impossible to put down, the simplicity and elegance of Rickwood Field, still intact 114 years after its genesis, causes us to forget about life’s worries and headaches, forcing us to live in the present.

ADVERTISEMENT

This week at Rickwood, living in the present also meant appreciating the past. It was easy to imagine the stories of the determined and brave Negro League players who stepped onto the field and left their world behind them. For as long as they were with each other, swinging a bat and smelling that stretch of green grass, then the outside world — painted with segregation, separate bathrooms and water fountains, protests about their participation in professional baseball, stepping aside for white people on the sidewalks, their self-worth oppressed — took a much-needed backseat.

At Rickwood Field, there was always joy in baseball that magnified over the Birmingham community. This Thursday, as Major League Baseball brought a major-league game to Alabama and Rickwood for the first time in history, all that glory stormed through the gates as soon as they opened.

Folks from the neighborhood were surprised and glad to run into each other at the concession stands, holding beers and cheeseburgers as they looked around, awestruck by the stadium’s magnificence.

[How Willie Mays is at Rickwood Field game ‘100 percent spiritually’]

Rickwood was renovated for this anticipated matchup between the San Francisco Giants and St. Louis Cardinals. There was an enormous black stage with live music greeting people into the grounds. The tops of the temporary fences, which were enhanced with iconic quotes from Negro League players like Buck O’Neill and Satchel Paige, were garlanded with pink, white and yellow flowers. The history of the Negro Leagues and the Black Barons were proudly displayed around every turn.

“I used to come out here in the early 1970s, so I had to bring my kids out here,” Ralph, a 67-year-old native of Birmingham told FOX Sports at Rickwood on Thursday. “Now my grandson plays high-school baseball, and they play their games here. So I come here a lot. But it’s different today. It feels more special.”

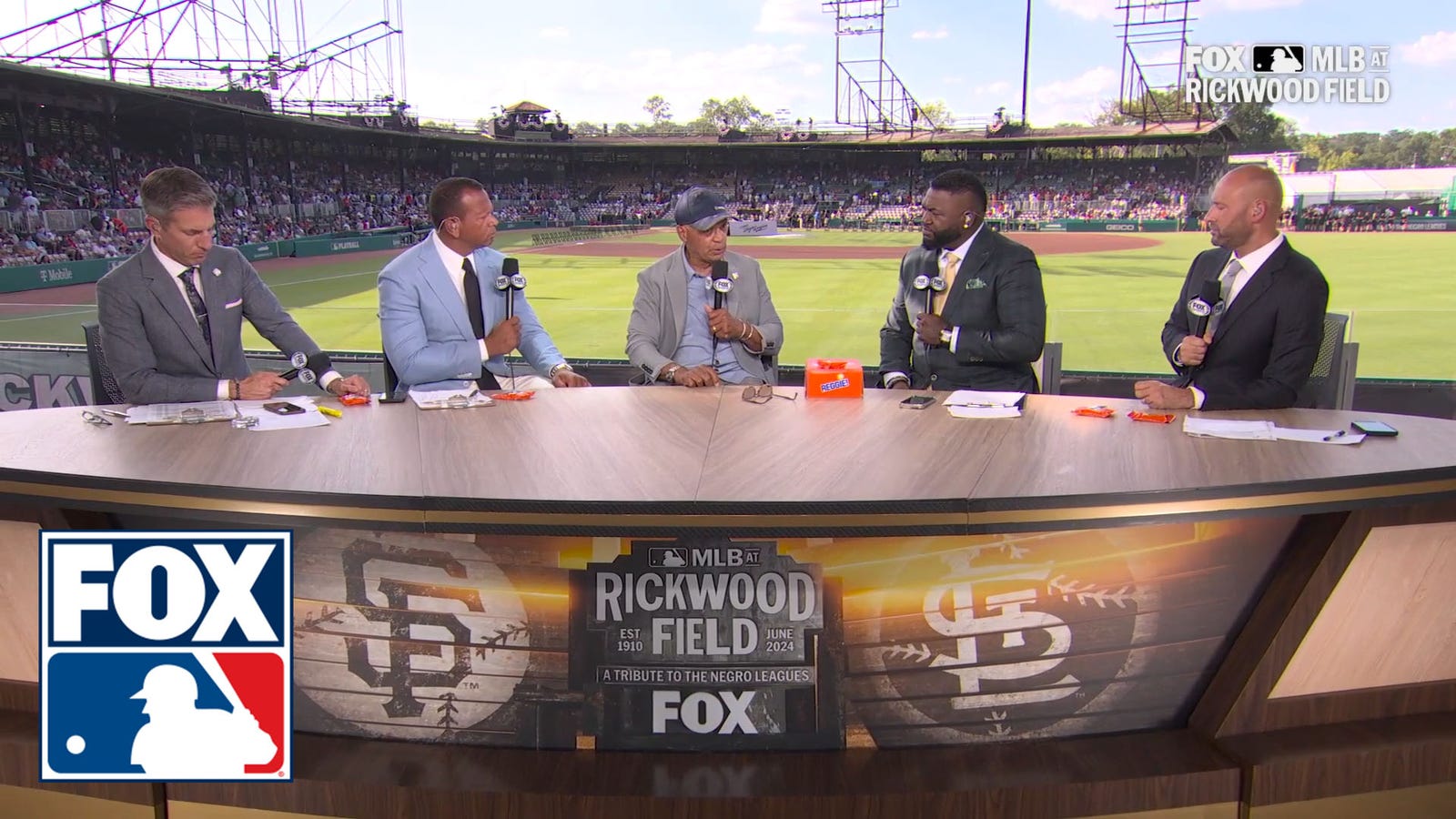

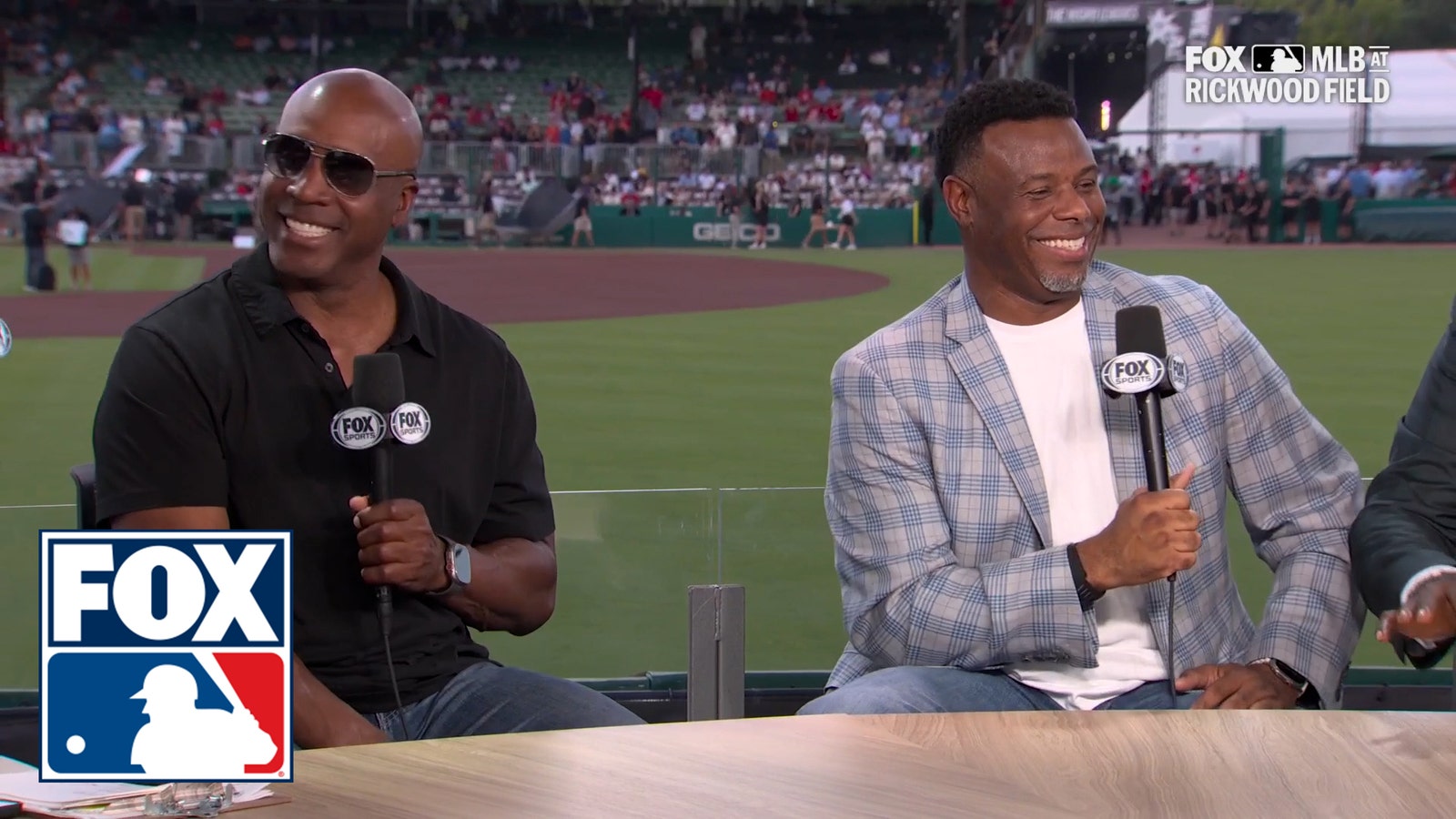

It was evident this day was more special just by the sheer volume of superstars and living legends, including 99-year-old former Negro Leaguer Bill Greason, who touched down in Birmingham.

Traveling into Rickwood wasn’t particularly easy or straightforward compared to the accessibility of modern ballparks. The surrounding neighborhood was underprivileged and unchanged, featuring many of the same, squat one-story houses that resembled the late Willie Mays’ childhood home in nearby Westfield. The surrounding blocks were closed off, and the neighborhood kids took advantage by playing and running in the streets. The closest parking was almost two miles away, so coach buses shuttled the crowd of 8,333 back and forth. Until people trickled into Rickwood and saw contemporary celebrities on the field, it was easy to mistake 2024 for the year 1910. The city was a throwback.

One of those celebrities within Rickwood was musician Jon Batiste, charged with the esteemed task of opening Thursday’s ceremonies. Batiste, wearing an off-white pinstriped Black Barons jersey with light-washed jeans, brought his hands together and clapped them in the air above him, once, twice, three times. He shook his hips violently and swung his legs side to side with no regard to rhythm or movement, but creating both in the process. Batiste wore a glowing white smile with every hop and step, a picture of the glory and joy Rickwood Field itself has forever represented.

From the cracks on the cement floor, to the brown and gray rustic wooden roof, Rickwood Field was a relic that established the meaning of being home. The ballpark was a mechanism for time travel and an escape from the outside world. As long as Rickwood keeps standing, we will all keep coming back.

Deesha Thosar is an MLB writer for FOX Sports. She previously covered the Mets as a beat reporter for the New York Daily News. The daughter of Indian immigrants, Deesha grew up on Long Island and now lives in Queens. Follow her on Twitter at @DeeshaThosar.

[Want great stories delivered right to your inbox? Create or log in to your FOX Sports account, follow leagues, teams and players to receive a personalized newsletter daily.]

recommended

Get more from Major League Baseball Follow your favorites to get information about games, news and more