LOS ANGELES — On a picturesque Friday evening in mid-October, a prominent Division I college football coach strides onto the field at Hilmer Lodge Stadium in Walnut, California, an eastern suburb of Los Angeles, to watch the top-ranked high school team in the nation — Mater Dei — embark on its latest demolition of an overmatched opponent. He’s wearing a white hooded sweatshirt, tan athleisure slacks and his trademark rimless glasses. His Nike sneakers are navy blue and white. Wherever he goes, an armed security guard follows.

After several minutes spent soaking in the action from the sideline, where he playfully chides the referees during timeouts, the coach winds his way across a track and into the bleachers where the family of four-star cornerback Daryus Dixson is seated near midfield. He claps three times before greeting Dixson’s mother, who sports a gray hoodie bedazzled with red letters and numbers across the chest and her son’s initials on the left sleeve. “How we doing?” he says with a grin. He shares a big hug with Dixson’s father and settles into the bleachers for a halftime chat.

It’s no secret why this coach is here the night before his team plays a highly anticipated game at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. Mater Dei, which will go on to finish its season undefeated, has a roster so stockpiled with talent that some of the underclassmen reserves already hold scholarship offers from Power 4 schools. The starting quarterback is committed to Washington. The starting cornerbacks are committed to Penn State and Alabama, respectively. The starting running back is one of three players who have given verbal pledges to Oregon, with a fourth who will join the Ducks by the end of the weekend. One of the wide receivers is being pursued by Ohio State, Texas, Oregon and Georgia. Another is committed to Oklahoma. A third, Chris Henry Jr., is the No. 1 overall player in the country for the 2026 recruiting cycle but suffered a torn ACL. He’s already committed to Ohio State. There’s a five-star sophomore tight end with scholarship offers from seemingly every blue blood imaginable.

While this is clearly one of the most talent-rich high school rosters in Southern California, which makes it a natural draw for local programs, the coach in attendance is not Lincoln Riley from USC — even though the Trojans have signed more players from Mater Dei (16) than any other high school in California since state-based recruiting data was first recorded in 2002, according to FOX Sports Research. Nor is it Riley’s crosstown rival at UCLA, first-year head coach DeShaun Foster, who was raised in nearby Tustin, California, and is attempting to reestablish the program’s local footprint. Instead, it’s Penn State head coach James Franklin, who earned a verbal commitment from Dixson, the No. 116 overall prospect and the No. 15 cornerback in the 2025 class, earlier this year.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Right now we don’t have an SC guy, you know?” first-year Mater Dei head coach Raul Lara said. “And it’s like, OK, what’s going on here? Again, to me, I think our schools need to do a better job here in California to keep the talent here.”

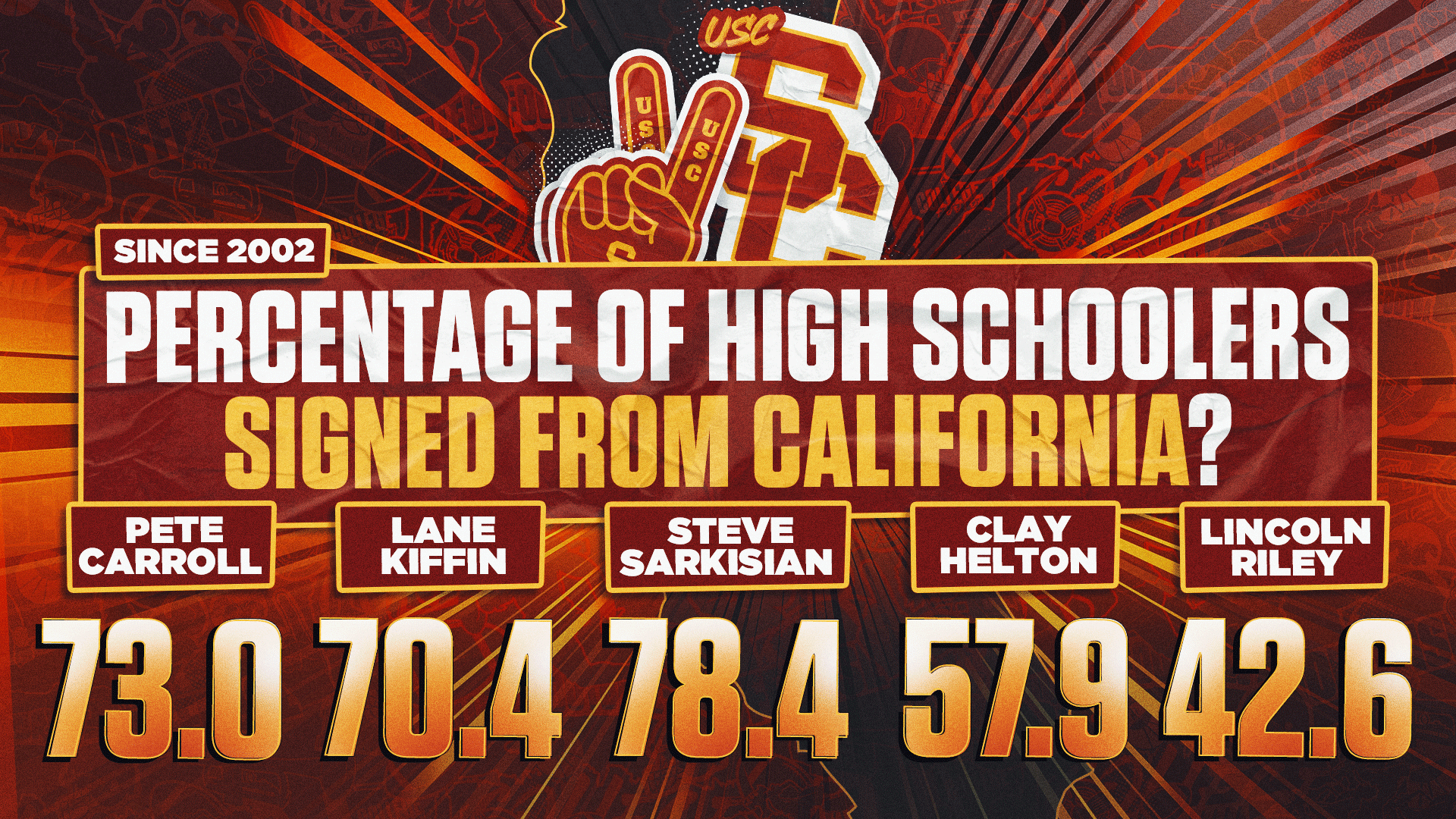

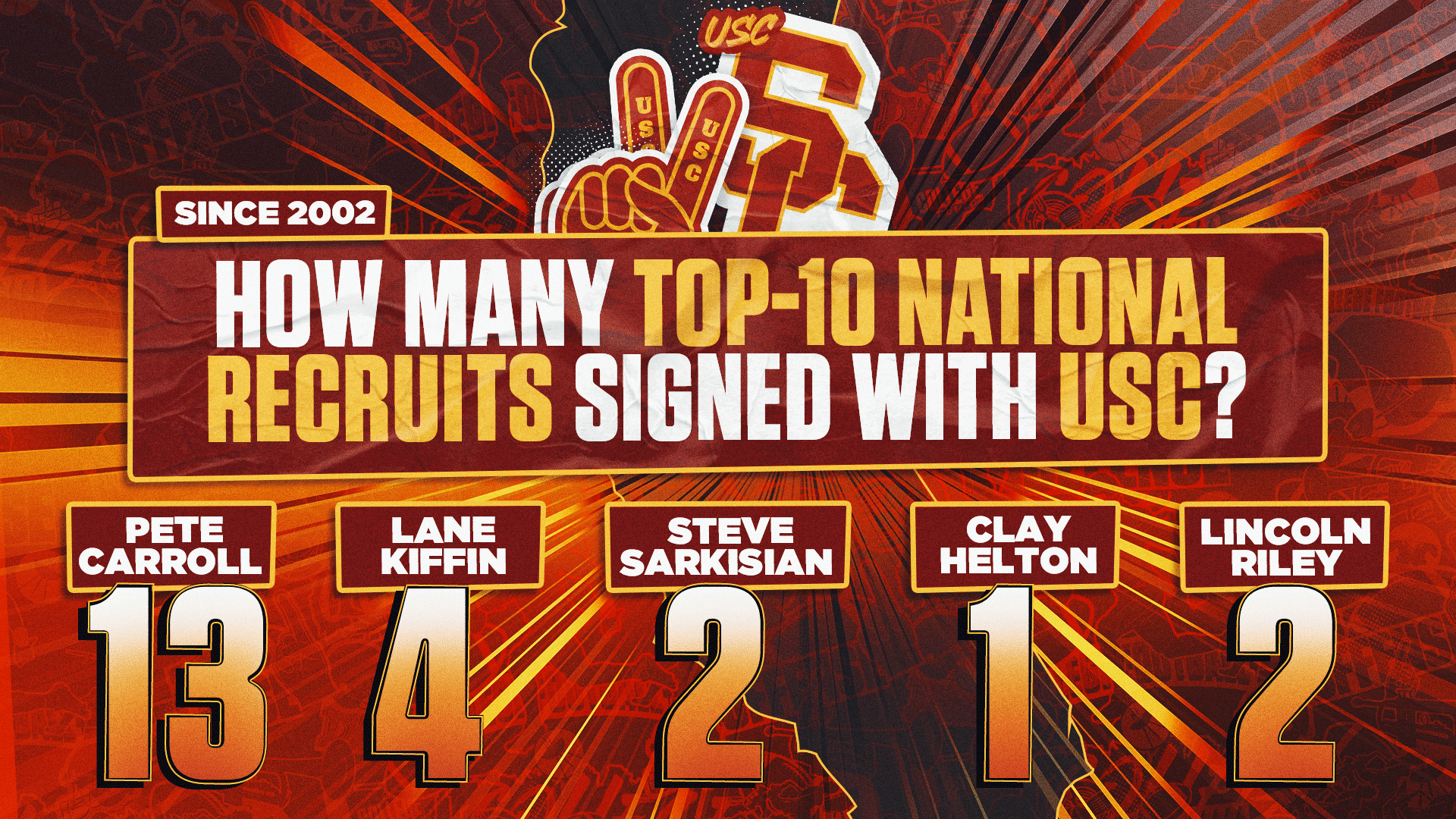

Keeping the talent in California was among the core philosophical tenets for former USC head coach Pete Carroll, who from 2001-09 assembled one of sport’s modern dynasties by winning two national championships, four Rose Bowls and stringing together seven consecutive seasons with at least 11 victories. More than 73% of the high schoolers signed by Carroll and his staff during that stretch came from California, including 40 recruits rated among the top 10 prospects in the state and four who finished their respective careers as the state’s best player. The average national ranking for USC’s recruiting classes while following that blueprint was 2.8, with the 2005 and 2006 groups both landing at No. 1 in the country.

Even after Carroll left to coach the Seattle Seahawks, the Trojans abided by the same formula under successors Lane Kiffin (70.4% from 2010-13) and Steve Sarkisian (78.4% from 2014-15), both of whom had spent time on Carroll’s staff in Los Angeles. And while the percentage of Californians began to dip under former coach Clay Helton, who only signed 58% in-state prospects during his time in charge from 2016-21, it’s the far more precipitous decline under Riley that continues to irk a more wistful segment of the fan base. That Riley is hovering around 42.6% Californians amid a three-year stretch in which the program’s win totals have regressed from 11 in 2022 to eight in 2023 and only six thus far in 2024 has fueled some of the wide-spread criticism lobbed in his direction.

“That’s just a constant at places like this,” Riley said.

Though some of the changes in roster construction can be attributed to the modernity of college football — with things like social media, nationally televised games and NIL compensation making it easier for prospects and their families to familiarize themselves with schools in other parts of the country — Riley is broadening his approach to high school recruiting by placing a greater emphasis on coast-to-coast player procurement. He and his staff don’t want to load up on in-state prospects during years when their evaluations point toward more talented recruits, or better culture fits, in other parts of the country. (It is worth noting, however, that they’ve found success adding California natives through the transfer portal in recent years.)

Still, there’s more pressure than ever for Riley to be right in 2025 after another lackluster season on the field and a fresh recruiting class that ranks 13th nationally, fourth in the Big Ten, and only includes three of the top 50 players in California as other elite programs cherry-picked most of the local talent. USC did earn the signature of five-star quarterback Husan Longstreet (No. 34 overall, No. 5 QB) from Centennial High School in Corona, California, after flipping him from Texas A&M last month, but the class features nearly as many Georgians (four) as in-state prospects (five).

“We’ve tried to come in here and be up-front and honest, you know, that we’re not necessarily going to take every single Southern California kid,” Riley said. “I mean, recruiting here is still a massive priority. It’s still the massive priority for us. But within that, it’s not just recruiting, it’s evaluating and making sure it’s the right kid from here. Because I do think it was our evaluation that maybe at times here, you know, the program had reached on some kids in this area that maybe if they were somewhere else, maybe they wouldn’t have necessarily recruited.”

*** *** ***

“Obviously there were some tremendous players where I came from [at Oklahoma], but it wasn’t a huge area and what would maybe be known as an incredibly fertile talent base. This is obviously a totally different experience. … We’ll certainly not just limit ourselves to that because we want to go get the best wherever they’re at, but I think there’s also a realization that a lot of the best are right here.”

— Lincoln Riley, introductory news conference, Nov. 29, 2021

From the balcony affixed to Riley’s second-floor office in the John McKay Center, a plot of land where the program’s new $200 million football facility will soon be built is easily visible. The three-story Bloom Football Performance Center, set to be completed in the summer of 2026, is slated to include a locker room and players’ lounge, a weight room with garage-door access to the practice fields, suites for sports medicine and nutrition, an array of team and positional meeting rooms, an NFL alumni locker room, a terrace replete with fire pits and ping pong tables, a walk-through practice area complete with digital technology and a room reserved for NFL scouts. Renderings of the new building are propped on easels throughout the hallways of the team’s current space, which is shared with most of the school’s Olympic sports, for players and recruits to admire.

“You’ll have to come back for the grand opening,” one of the communications representatives says to a visiting reporter.

Preliminary rendering of USC’s Bloom Football Performance Center, set to be completed in the summer of 2026. (Photo courtesy of USC Athletics)

On this Thursday morning in mid-October, at which point the Trojans are one game into an eventual three-game losing streak, there are parallels to be drawn between the upturned soil where the breathtaking new facility will be located and the prolonged roster overhaul that Riley continues to oversee. Riley described the situation he inherited at USC as “broken down a little bit,” with noteworthy deficiencies in facilities, fundraising, staffing, NIL coordination and, most glaringly, roster construction — especially once news broke in June 2022 of the program’s impending shift to the Big Ten, a conference known for its ruggedness in the trenches. The Trojans’ average national recruiting class ranking had slipped from an average of 4.4 under Carroll, Kiffin and Sarkisian to 17.2 under Clay Helton, who notched 21 wins over his first two seasons before the program slipped into disarray from 2018-21, a stretch in which the Trojans only won 22 games combined. Included in that time was the school’s century-worst 2020 recruiting class, which ranked 59th overall and only included one player ranked among the top 345 overall. Riley’s first three classes have ranked 70th in 2022, eighth in 2023 and 17th in 2024.

Within eight months of arriving at USC on Nov. 28, 2021, Riley hired the man with whom he works closest to shape the future of the program: Dave Emerick. Operating out of a much smaller office down the hall, Emerick joined Riley’s staff as the senior associate athletic director for football/general manager in July 2022 after spending the previous 10 years under the late Mike Leach, first at Washington State and then at Mississippi State. He serves as the conduit between coaches and the personnel department, which includes five full-time staffers focused on studying high school prospects and transfer targets, and the recruiting department, which consists of four staffers who handle visits and correspondence with prospective players. Members of the personnel department conduct the first round of player evaluations and then watch film with the coaches to better understand what Riley and his staff are looking for. Emerick, who has become a lightning rod figure among disgruntled fans, connects the dots by spending his days on the phone with recruits, parents, agents and coaches.

“I think having somebody else in the building that has had to be responsible for all these other parts was important,” Riley said, “because you can get people that are really good, but they have tunnel vision. They see their area, but they don’t always see the big picture. I feel like Dave, because of his experience, is able to see the big picture. And I think that allows him to do his job at a high level.”

The recruiting strategy that Riley and Emerick developed is in keeping with what they describe as the uniqueness of USC, a rigorous academic institution that blends its bustling metropolis backdrop with a highly scrutinized football program that has produced 557 NFL draft picks, eight Heisman Trophy winners and captured 11 national championships. Finding prospects who can succeed in that environment has led Riley to “a smaller pool” of players than he had grown accustomed to pursuing in previous jobs, but it allows the Trojans to cast a wider net geographically and spend more time getting to know individual recruits. Riley’s 2025 class includes players from Maryland, Missouri, Oklahoma, Utah, Virginia and Washington, in addition to states more commonly recognized for their recruiting exports. Overall, the number of states represented in USC’s classes under Riley has increased every year, from four in 2022 to 12 so far in the current cycle. Meanwhile, Carroll’s classes from 2002-09 were represented by an average of just 5.75 states per year, including an ’03 group that still ranked No. 2 in the country despite only signing players from California (24), Colorado (1) and Louisiana (1).

Whether by choice or an inability to win recruiting battles — or, perhaps, both — the current USC staff has become far less reliant on in-state prospects, much to the chagrin of longtime fans. Riley’s first recruiting class included the two highest-rated recruits from California in five-star cornerback Domani Jackson (No. 5 overall, No. 2 CB) and four-star tailback Raleek Brown (No. 42 overall, No. 3 RB), but both players wound up transferring. Since then, the Trojans have only signed nine of the state’s top 75 players over the last three recruiting cycles combined as rivals like Oregon (16 signees) and Alabama (eight signees) continue raiding the area with eye-catching success. The Crimson Tide have already secured three of the six highest-rated players in California for the 2025 cycle.

USC plans to stay the course.

“We’re not just going to take a guy because he’s from California,” Emerick said. “I do think that [the] willingness of outside guys to come in and [the] willingness of California kids to leave has increased as the NIL era has changed things. But our first priority is keeping these local kids that we want here — and then going from there and building the class around those guys.”

*** *** ***

“Our recruiting efforts are to find those special kind of competitors, those people that always reach for the top. We look for ways to develop those people when they show they have those capabilities. When I think of the tradition and I set forth with what we are going to do in the program, it is to find people that match that vision.”

— Pete Carroll, introductory news conference, Dec. 15, 2000

During the nine seasons Carroll spent at USC, he developed a tradition for National Signing Day that involved the current players who would be returning the following year. It began with everyone gathering in a team meeting room once the letters of intent from incoming freshmen had been received. And then Carroll, known throughout his career as a master motivator, would roll highlights of all the signees and explain just how quickly the ultra-talented newcomers would be pushing the veterans for playing time. The room always erupted with trash talk and cheers.

“Culture before scheme,” said Norm Chow, the Trojans’ offensive coordinator from 2001-04. “And that was the way that group was.”

It was one of many ways Carroll incubated a culture of competition based on his obsession with the Latin root of the word — competere — which means to strive together rather than striving against. After being fired as head coach of the New England Patriots following the 1999 season, Carroll had spent a year out of football preparing for his next job. He read a book by legendary UCLA basketball coach John Wooden titled “A Lifetime of Observations and Reflections On and Off the Court” and became obsessed with finding ways to replicate that level of success. He filled notebook after notebook, yellow legal pad after yellow legal pad, with ideas for what he wanted each day of the week to look like whenever he returned to coaching. At least three people passed on the USC job before the school hired Carroll, who hadn’t worked at the collegiate level since 1983, in a move that was loudly criticized by local media.

Carroll laid the groundwork for the recruiting dominance to come by retaining assistants Ed Orgeron and Kennedy Polamalu from the previous staff. The former, who would go on to win a national championship as head coach at LSU in 2019, bridged the gap with local high school coaches and prospects while Caroll and the newcomers got acclimated to Los Angeles. The latter, who is now the running backs coach for the Seahawks, was responsible for outlining the “idea of what recruiting at USC should be like,” according to Chow. And what Polamalu envisioned was putting an impenetrable fence around California.

“I think we were always looking to get the best kid, the best player in the state of California,” said Yogi Roth, the quarterbacks coach at USC from 2005-09. “And if we ever left the state, it was for what we deemed to be a possible first-round draft pick. It was really clear in that regard.”

The player that Chow believes turned the tide for USC’s recruiting efforts — a prospect he described as “the pied piper” — was defensive tackle Shaun Cody, a five-star recruit from Los Altos High School in Hacienda Heights, California, an eastern suburb of Los Angeles. Cody was rated the No. 1 defensive player in the country and a top-five recruit regardless of position when the Trojans flipped him from Notre Dame, setting in motion an avalanche of in-state success so dominant that it eventually spawned jokes about coaches from other programs only visiting California for vacation; trying to pry local stars away from USC was considered a waste of time. As Caroll’s team accelerated from a 6-6 outfit during his first season to hoisting the national championship trophy in his third, the Trojans were transformed into one of the city’s must-see attractions for recruits and celebrities alike.

From 2003-06, Carroll secured the state’s No. 1 player in four consecutive classes and signed at least four of the state’s top-10 prospects in each of those cycles. He inked three five-star running backs from California in ’06 alone — Stefon Johnson (No. 10 overall), Allen Bradford (No. 17 overall) and C.J. Gable (No. 26 overall) — to headline a class that included 10 of the state’s best 19 players overall. USC averaged 13.9 in-state signees per year under Carroll from 2002-09, a stretch that coincided with 91 victories on the field. So magnetic were Carroll and the Trojans to local prospects that his assistant coaches began to feel like evaluators more than recruiters. Their only task was to identify the best players because everyone wanted to come.

“The way [Carroll] entered a room, the way he talked to me was very like, ‘Hey, we’re going to conquer the world,’” said former USC and Long Beach Poly offensive tackle Winston Justice, a five-star recruit and the No. 32 overall player in the 2002 recruiting cycle. “And as a young kid from Long Beach, California, if someone is telling you, ‘Hey, I want to conquer the world,’ you wanted to do that with him, you know?”

It’s the same reason why actor Will Ferrell was a frequent guest at USC’s practices, where he was known to throw the ball around with players. It’s the reason why rapper Snoop Dogg became a mainstay on the sidelines and once engaged in a freestyle battle with cornerback Eric Wright. It’s why Roth created what he believes was the first-ever college football blog focused on bringing fans behind the scenes of team meetings and other intimate moments. Everyone wanted to see what the Trojans were doing as they became synonymous with Hollywood and morphed into a cultural phenomenon in the pre-social media era.

“Being a SoCal kid playing at USC,” said Mark Sanchez, a five-star quarterback at Mission Viejo High School and the No. 3 overall player in the 2005 recruiting cycle, “that was a big deal.”

*** *** ***

So what happened?

More than a dozen interviews with former coaches, players, recruits, USC staffers and industry experts point toward a confluence of factors that contributed to the program’s regression and subsequent shift in roster-building philosophy once Carroll departed. His immediate successors, Lane Kiffin and Steve Sarkisian, adhered to the same California-based recruiting strategy that Carroll had devised, with both men signing more than 70% in-state prospects across six combined classes. But things began to change when the NCAA handed down a stiff batch of sanctions in June 2010 — a two-year postseason ban, significant scholarship reductions and more than a dozen vacated wins from the Carroll era, the main impetus for which were impermissible gifts accepted by Heisman Trophy-winning tailback Reggie Bush — that chipped away at the Trojans’ infallible mystique. With only two 10-win seasons from 2010-15, neither of which resulted in trips to a BCS bowl game, USC’s allure among local prospects began to wane.

The program’s vice grip on in-state recruiting was further eroded by the digitalization of player acquisition in college football. Applications like Hudl, YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and FaceTime catalyzed the simultaneous flow of information from players in every part of the country to coaching staffs thousands of miles away. Suddenly, prospects could begin to form connections with schools they’d never even visited simply by being connected to their phones. And once the NCAA approved name, image and likeness (NIL) legislation in July 2021, opening the door for recruits and their families to have travel expenses covered and even be compensated for taking official visits, the idea of playing somewhere other than USC became increasingly appealing to many local recruits.

“It’s a great program,” said four-star linebacker Noah Mikhail, a native of La Verne, California, who took an official visit to USC before signing with Texas A&M earlier this week. “But I think just class-based it’s [about] what people are really looking for. And for a lot of us in Cali, it’s an out-of-state program.”

Which is one of the reasons why Riley and his staff have swung — and swung big — in other parts of the country since taking over the program, aiming to capitalize on what defensive coordinator D’Anton Lynn described as an eye-widening effect whenever recruits see coaches in SC gear visiting their school. At one point or another during the 2025 cycle, the Trojans held verbal commitments from six non-Californians now ranked among the top 60 players in the country, including a trio of five-star prospects. But none of the six wound up signing with USC, and another borderline five-star prospect — quarterback Julian Lewis from Georgia — was committed to the Trojans for more than a year before flipping to Colorado last month.

For fans that had grown accustomed to top-notch recruiting, each out-of-state misfire is compounded by Riley’s inconsistent efforts on the home front, where Alabama and Texas A&M both signed more top-10 players from California in this year’s class than the Trojans did. There is supreme pressure on USC’s coaching staff and NIL collective to push those high-profile, out-of-state recruitments across the finish line if they aren’t being buttressed by a safety net of local stars.

“USC has shown they can commit those guys,” said Steve Wiltfong, vice president of national college football recruiting at On3 and the former director of recruiting at 247Sports. “But they have not shown they can sign those guys just yet.”

There are, of course, exceptions to that general rule — and with Wednesday afternoon came a big one when the Trojans landed five-star defensive lineman Jahkeem Stewart (No. 16 overall, No. 3 DL) from Louisiana. The only higher-rated non-Californian signed by Riley during his time at USC is former five-star wideout Zachariah Branch, a Nevada native and the No. 4 overall prospect in the 2023 cycle.

But even with Stewart’s signature, it’s possible that the program’s biggest recruiting victory in recent weeks took place on Nov. 8, when a staffer from national powerhouse Mater Dei posted a photo on social media of Riley visiting the campus. Head coach Raul Lara called the meeting “a great start to our relationship,” during a brief interview with the Orange County Register.

And perhaps that’s Riley’s first step toward reclaiming California.

“You have to have enough confidence and belief in your setup, your people and going through your process for what you know wins,” Riley said. “And if you keep doing those things, then eventually — whether [it’s] next week, next year, whenever — eventually the results that you want and your supporters and all that want, eventually it shows up.”

— College football editor Sean Merriman contributed reporting.

Michael Cohen covers college football and basketball for FOX Sports with an emphasis on the Big Ten. Follow him at @Michael_Cohen13.

recommended

Get more from College Football Follow your favorites to get information about games, news and more