Former Baylor football coach Art Briles was not negligent in the case involving a female student who reported being physically assaulted by one of his players in 2014, a federal judge ruled Friday.

U.S. District Judge Robert Pitman dismissed the gross negligence claims against Briles, along with former athletic director Ian McCaw and Baylor University, saying “no reasonable jury can conclude” based on the evidence presented at trial that the defendants were “grossly negligent.”

The plaintiff, former Baylor student Dolores Lozano, had claimed that the three defendants’ negligence after she reported her first assault in March 2014 made her subject to further abuse by football player Devin Chafin, whom she had been dating.

“This case was always about Ms. Lozano getting her day in court,” Pitman said Thursday, but after hearing the evidence, he said there simply wasn’t enough there to convince a jury. That leaves a Title IX claim and one negligence claim against Baylor as the only matters to be given to the jury, which reconvenes Monday. Lozano has alleged that the school’s overall failures to address and properly respond to reports of sexual violence at that time put her at greater risk for assault and was a violation of Title IX.

“The judge said this has always been about Ms. Lozano having her day in court. We agree,” said Lozano’s attorney Sheila Haddock. “The judge granted Baylor’s motion solely on the issue of gross negligence. He denied the remainder of Baylor’s motions and we look forward to presenting our case to the jury on Monday.”

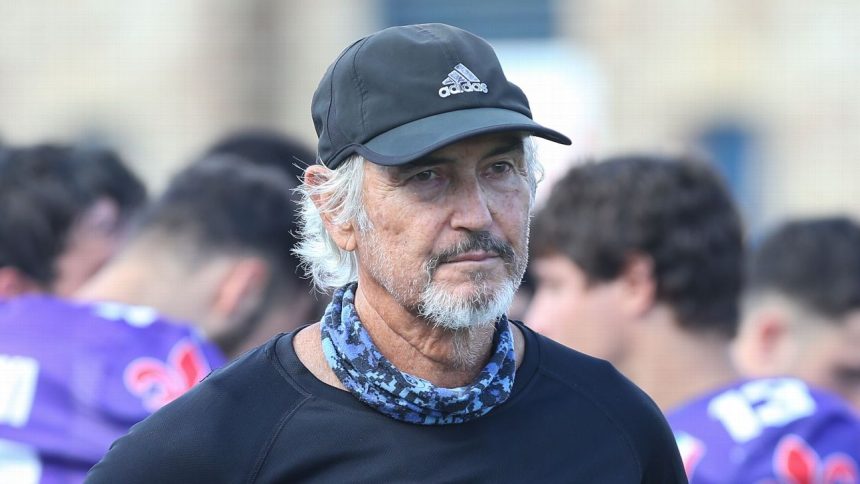

McCaw and Briles testified Thursday. McCaw said that when he received a report of Lozano’s allegations from one of his staff members in 2014, he took appropriate action and made sure she had been given information on how to further report it. Briles said he simply didn’t know anything about Lozano or her reports against Chafin until she filed her lawsuit in 2016. He said he had never communicated with Lozano.

Reid Simpson, an attorney for Briles, was on the courthouse steps standing before reporters Friday morning on the phone with Briles to share the news. “I appreciate you,” Briles could be heard saying over speakerphone.

“Everything that’s been said about him is not true,” Simpson said. During the trial, Simpson’s questioning of witnesses often came back to a series of questions about whether there was any evidence that Briles covered up sexual assault, deterred victims from reporting assaults or tried to interfere with investigations, and the witnesses denied knowing of any of those actions.

When asked if Friday’s ruling would help Briles’ reputation in the wake of the investigations in 2016 that led to his firing, Simpson said, “I hope it helps.”

McCaw’s attorney, Thomas Brandt, said he was pleased with the ruling, but he said the decision means “nothing” in regard to the wider sexual assault failings at Baylor and McCaw’s involvement.

The law firm Pepper Hamilton, which investigated the school’s handling of sexual violence reports in 2015 and 2016, had access to dozens of reports and used five of them — all involving football players — in its presentation to the Baylor regents in May 2016. Lozano’s domestic violence case was not among them.

In her opening statement to jurors Monday, Baylor attorney Julie Springer acknowledged the school’s history with sexual violence victims and the 2016 results of the investigation that uncovered failures in responding to and reporting incidents of sexual violence throughout the university.

“There is no question that bad things happened and mistakes were made at Baylor. Baylor accepts and accepted responsibility for those failures,” she said. “This case is not one of the cases in the [investigation] findings. In Dolores Lozano’s case, Baylor got it right.”