Meet Mr. Irrelevant, 1969.

He was drafted by the New York Jets — No. 442 overall — and enjoyed a long, fruitful career. At 6-foot-4, 245 pounds, he was an intimidating presence, a natural leader and supremely confident. He prided himself on outworking the competition, allowing him to reap handsome financial rewards.

His name is Fred Zirkle, and he never played a down in the NFL. Never showed up for training camp, as a matter of fact.

He resisted the lure of professional football, spurned the reigning Super Bowl champions and followed his heart instead of the crowd. He chose business as his career, not football, becoming a wealthy entrepreneur and investment banker with a net worth that ranks in the top 5% of Americans.

Why are we telling you about Fred Zirkle? It’s draft season and, for the first time since 1969, the Jets own the last pick (No. 257), a compensatory selection. Barring a trade, they will crown the latest Mr. Irrelevant, the celebrity long shot who owns a place in American sports culture. Brock Purdy‘s success as San Francisco 49ers quarterback has raised the Mr. Irrelevant profile since he was drafted in 2022.

The enduring charm of the draft — and its bane — is it’s filled with “what-might-have-been” stories. Zirkle is one of those, although not in the conventional sense. He pulled a Robert Frost, taking the road less traveled. He doesn’t regret his choice, leaving football behind after college, but there are occasional stabs of remorse.

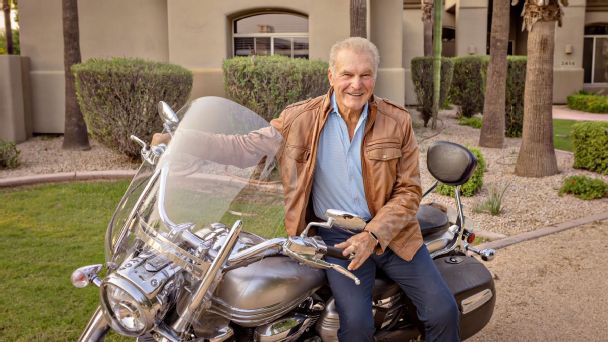

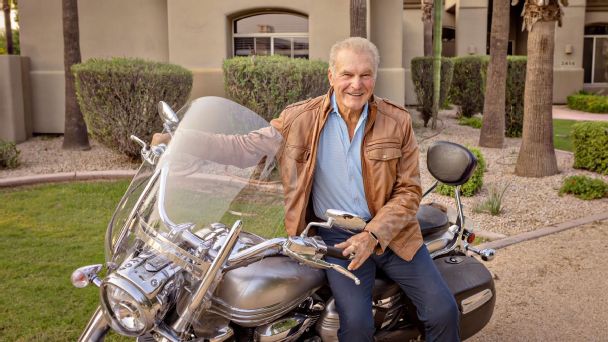

“Yes, I definitely experienced that,” Zirkle, 78, said by phone from his home in Chandler, Arizona. “I actually have dreams that the New York Jets called me — this is 30 years later — and they’re saying, ‘Hey, we need you.’ … I still have dreams and wonder how I would’ve done.”

ZIRKLE WAS A defensive tackle at Duke, served as a team captain and participated in the Blue-Gray Football Classic, a now-defunct college all-star game. Former Duke teammate Al Woodall, a quarterback also drafted by the Jets in 1969, recalled Zirkle this way: “A huge guy with a big head and a square jaw. He was just an imposing-looking guy. You didn’t want to run into him in the wrong place.”

In the common draft era (since 1967), 25 of the 57 players picked last managed to appear in at least one regular-season game — 44%, according to Pro Football Reference. In Zirkle’s day, the odds were longer because the draft was 17 rounds. It was cut to 12 in 1977 and seven rounds in 1997.

It would have been difficult to make the Jets’ roster as a 17th-round pick. The team was loaded with talent, having just pulled off one of the biggest upsets in sports history against the Baltimore Colts in Super Bowl III.

On the other hand, running back George Nock — picked in the 16th round — made the roster. So anything was possible.

“I didn’t want to be a has-been at age 35,” said Zirkle, explaining why he passed on the NFL

There was more to it than that.

A business administration major at Duke, Zirkle was hell-bent on tackling the corporate world. Even though college players and pro scouts weren’t allowed to communicate in those days, he got word to many of them that he didn’t want to be drafted. The Jets “followed the rules,” Zirkle recalled, which explains why they didn’t get wind of his wishes.

So, yes, he was shocked when he learned from a sportscaster that he had been drafted — last. (The first overall pick that year was O.J. Simpson.) There was no fanfare because “Mr. Irrelevant” wasn’t coined until 1976. Eventually, he told the Jets, “Thanks, but no thanks.” He considered it an honor to be drafted.

“Everyone — the whole country — was excited about the Jets,” Zirkle said. “Namath was so colorful and the Jets were just coming into their own. We all identified with the Jets as a group that played football and pulled off some surprising wins.”

FIVE DECADES LATER, Zirkle laughed as he recalled being in Manhattan for a job interview that summer after being drafted and seeing his name mentioned by coach Weeb Ewbank in a newspaper article. He was there to meet with former Duke classmate John Mack, the future president of Morgan Stanley, for a position at the investment firm Bear Stearns.

After the interview, they repaired to a watering hole, where they came across a newspaper story about Jets training camp. Ewbank was quoted as saying that Namath and Zirkle still hadn’t reported to camp, which Zirkle found hilarious.

Even though he never played for the Jets, he can say his name appeared in the same sentence as the legendary quarterback, who had briefly retired because of a dispute with the NFL over a Manhattan nightclub that he owned.

Zirkle became a footnote in Jets history, so obscure that former public relations director Frank Ramos — the franchise’s de facto historian — has no recollection of him.

“No, I don’t, but good for him,” said Ramos, the team’s PR man from 1963 to 2002. “I’m glad he’s doing well.”

In that era, Ramos noted that some players worked a second job during football season to make ends meet. In 1969, the minimum salary for rookies was less than $12,500; it increased to $12,500 in 1970, according to the NFL Players’ Association. Based on inflation, that’s the equivalent of $104,000 today.

Zirkle was singularly focused, bypassing the Jets (not to mention graduate school at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania) to start a company with his father.

He became the president and CEO of Key Tronic, a computer hardware company that generated a reported $180 million in annual revenue. He later was the president of Alpnet (computer software) and VentureSum (venture capital). All told, he has bought and sold businesses in 11 different countries.

Currently, he’s the CEO of Industry Pro, an advisory firm he founded that assists companies that want to buy and sell. Zirkle has 25 employees and has closed more than $2 billion in transactions since its inception in 1991, according to its website. His son, Zach, handles the day-to-day operation.

Zirkle is currently writing a book, entitled, “Life’s ROI” — return on investment. Sharing his business philosophy, he used a football analogy.

“What I learned in football was just keep moving,” Zirkle said. “If you find you’re blocked in one way, swing around and go through another path. That’s been my career.”

He’s been moving and shaking his entire life.

In high school, in Blacksburg, Virginia, he trained for track meets by running in heavy boots through the mountains and chasing cows. (He said he once ran 400 meters in 51 seconds.)

While playing for Duke, he was so fired up for a game at Michigan that he broke five facemasks in practice, including two of his own, and before a game against Georgia Tech, he delivered a players-only pep talk, during which they decided to ignore the coaches and call their own plays.

It was risky, but Duke won, and Zirkle received a most inspirational player award from an alumni group.

Because of cranky knees, Zirkle’s activity nowadays is limited to riding an electric bike on the trails of the San Tan Mountains near his home. He does it every day, 10 miles. At home, he has a hammock amid the palm trees, with a pool, a pond and blue skies. He calls it paradise in the desert.

He doesn’t follow the NFL. He believes his life is complete without it, which means nothing has changed from the time he was 22, when the draft was held two weeks after the Super Bowl. But it’s nice knowing that, once upon a time, the NFL wanted him.

“At the time, Mr. Irrelevant hadn’t been coined yet,” Zirkle said. “But I always felt it was an honor to be drafted.

“Even at No. 442.”